I wanted to share two simple arguments for God's existence that I don't see used very often :the argument from intelligibility, and the argument from desire.

I. The Argument from Intelligibility

In 1968 a young theology professor at the University of Tübingen formulated a neat argument for God's existence that owed a good deal to Thomas Aquinas but also drew on more contemporary sources. The theologian's name was Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI. Ratzinger commences with the observation that finite being, as we experience it, is marked, through and through, by intelligibility, that it is to say, by a formal structure that makes it understandable to an inquiring mind.

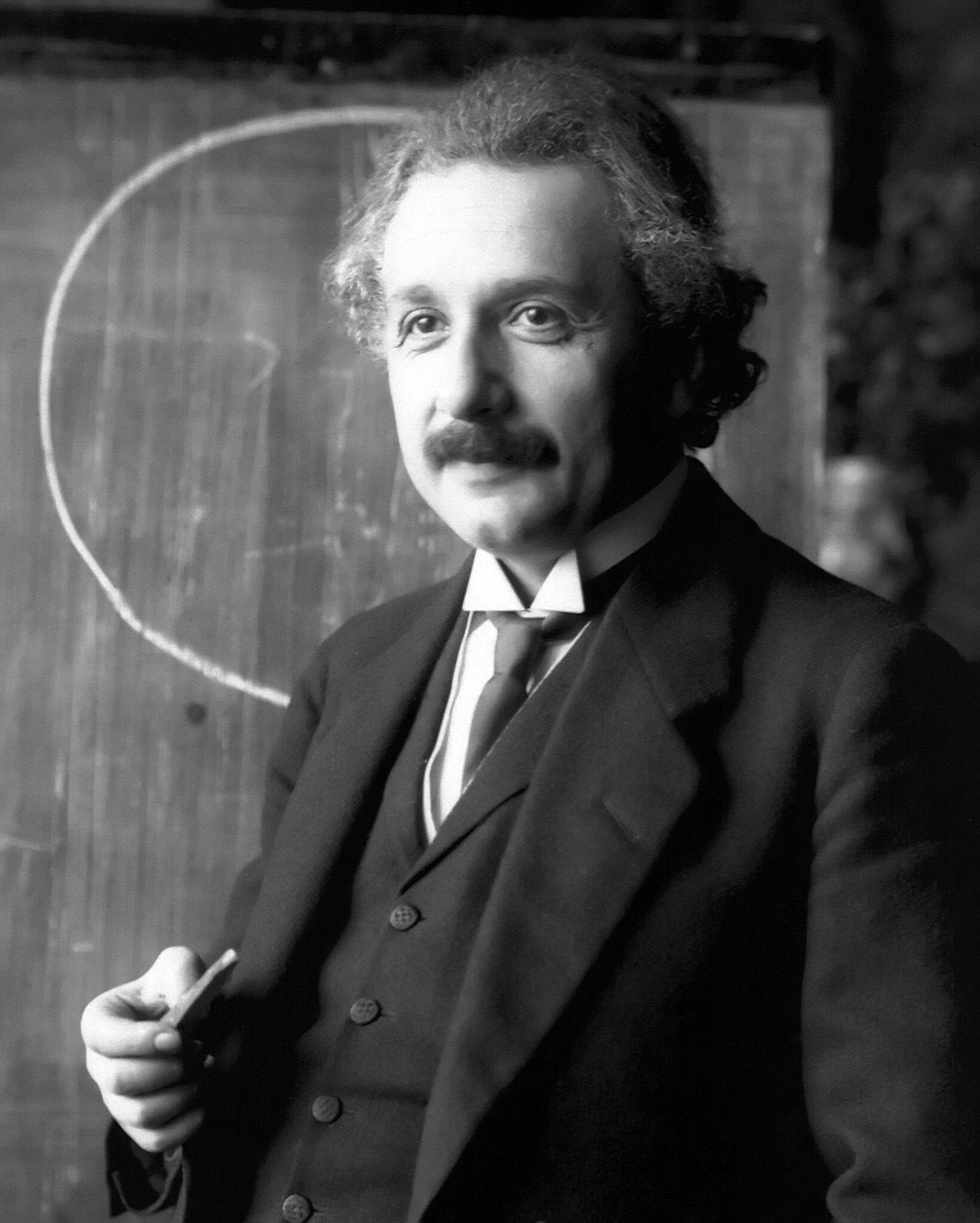

Pope Benedict XVI

In point of fact, all of the sciences - physics, chemistry, psychology, astronomy, biology, and so forth - rest on the assumption that at all levels, microscopic and macroscopic, being can be known. The same principle was acknowledged in ancient times by Pythagoras, who said that all existing things correspond in numeric value, and in medieval times by the scholastic philsophers who forumlated the dictum omne ens est scibile (all being in knowable).

Ratzinger argues that the only finally satisfying explanaiton for this universal objective intelligibility is a great Intelligence who has thought the universe into being. Our language provides an intriguing clue in this regard, for we speak of our acks of knowledge as moments of “recognition,” literally a re-cognition, a thinking again what has already been thought. Ratzinger cites Einstein in support of this connection: “in the laws of nature, a mind so superior is revealed that in comparison, our minds are as something worthless.” The prologue to the Gospel of John states, “In the beginning was the Word,” and specifies that all things came to be through this divine Logos, implying thereby that the being of the universe is not dumbly there, but rather intelligently there, imbued by a creative mind with intelligible structure.In other words, all science points to God, since all science requires intelligibility, which in turn, requires an Intelligent Creator.

|

| Einstein |

By the way, while Benedict developed this argument, we see variations of it being made back in the early days of the 300s, when St. Athanasius argued that “if the movement of creation were irrational, and the universe were borne along without plan, a man might fairly disbelieve what we say. But if it subsist in reason and wisdom and skill, and is perfectly ordered throughout, it follows that He that is over it and has ordered it is none other than the [reason or] Word of God.” So the argument has a pretty solid pedigree, such as it is.

II. The Argument from Desire

C.S. Lewis (in his second appearance on the blog this week) describes the argument from hunger this way, in Mere Christianity (pp. 136-37):

The Christian says ‘Creatures are not born with desires unless satisfaction for those desires exists. A baby feels hunger: well, there is such a thing as food. A duckling wants to swim:: well, there is such a thing as water. Men feel sexual desire: well, there is such a thing as sex. If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world. If none of my earthly pleasures satisfy it, that does not prove that the universe is a fraud. Probably earthly pleasures were never meant to satisfy it, but only to arouse it, to suggest the real thing. If that is so, I must take care, on the one hand, never to despise, or to be unthankful for, these earthly blessings, and on the other, never to mistake them for the something else of which they are only a copy, or echo, or mirage. I must keep alive in myself the desire for my true country, which I shall not find till after death; I must never let it get snowed under or turned aside; I must make it the main object of life to press on to that other country and to help others do the same.’This argument is self-explanatory, but let me answer two objections.

|

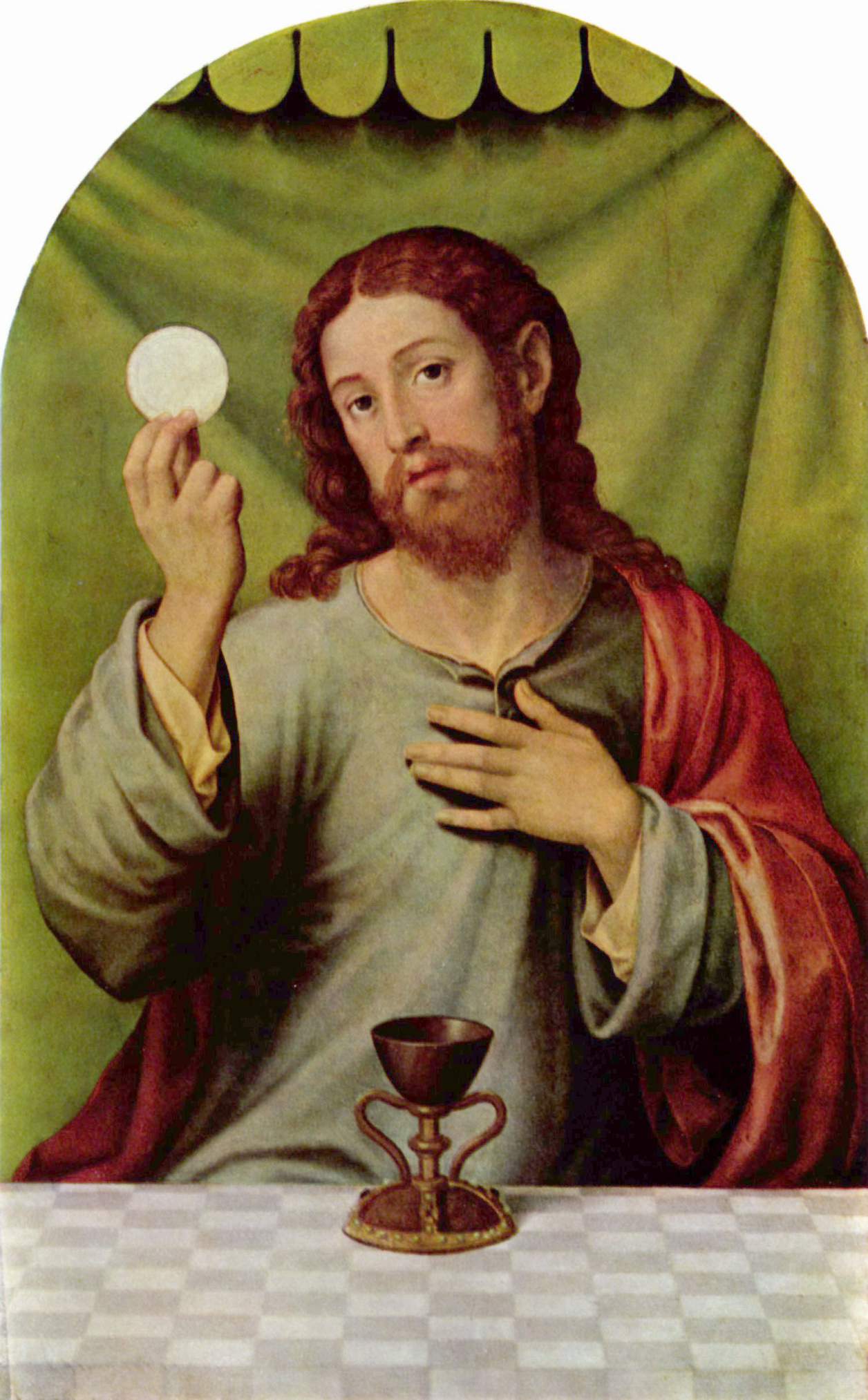

| Juan de Juanes, Jesus with the Eucharist (mid-16th c.) |

Second, while our desires correspond to realities, but they can be corrupted and perverted. Gluttony is a perversion of our natural desire for food, lust is a perversion of our natural desire for sex, and so on. But standing back, we can see why hunger (and gluttony) exist, and why sexual desires (and lust) exist. These are desires that are ordered towards the attainment of specific goals. So even if the hunger for God gets perverted in some way, this doesn't deny the reality that God exists, and that we long for Him.

Finally, with our desire for God, the appropriate question ought to be: could anything less than God possibly satisfy this hunger? We try to appease that hunger for God by substituting earthly pleasures: wealth, honor, power, and sensible pleasures (everything from sex to overeating). But that's like drinking a lot of water when you're hungry for food. It might fill the void for a while, but it doesn't really satisfy the craving. Our souls are made with an aching hunger for God.

No comments:

Post a Comment